John D. Rockefeller: The Architect of Modern Capitalism and the Standard Oil Empire

Early Life: Forged in Discipline and Ambition

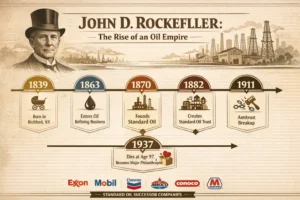

John Davison Rockefeller entered the world on July 8, 1839, in the modest farming community of Richford, New York—a place far removed from the glittering centers of power he would one day command. His upbringing was a study in contrasts that profoundly shaped his worldview. His father, William Avery Rockefeller, was a charismatic but unreliable traveling salesman and occasional con man, known for sharp (and sometimes shady) business dealings that prioritized profit above all. This instilled in young John a pragmatic, no-nonsense approach to commerce, where cunning and opportunism were survival tools. In stark opposition stood his mother, Eliza Davison Rockefeller, a devout Baptist whose life revolved around religious austerity, frugality, and methodical charity. She taught him the virtues of hard work, meticulous record-keeping, and the idea that wealth was a divine stewardship to be managed responsibly—a philosophy that would later fuel both his empire-building and philanthropy.

By age 12, Rockefeller was already demonstrating prodigious talent for numbers, lending money to neighbors at interest and tracking every penny in a personal ledger. At 16, he landed his first job as a bookkeeper for a Cleveland produce commission firm, earning $50 a month (later $3.50 a day)—a princely sum for the era. He obsessively logged every expense, from streetcar fares to charity donations, cultivating an unyielding focus on precision, cost-control, and long-term planning. Cleveland, a burgeoning hub with lake access and rail links, positioned him perfectly as the 1859 Titusville oil strike in Pennsylvania ignited the “oil rush.” While speculators chased volatile drilling fortunes, Rockefeller astutely identified refining—the stable process of converting crude into kerosene for lamps—as the real opportunity. Avoiding the boom-bust drilling risks, he entered as a commission merchant trading grains and produce before investing in his first refinery in 1863 with $4,000 (half borrowed). This move sidestepped the chaos, capitalizing on kerosene’s skyrocketing demand in a pre-electricity world.

Founding Standard Oil: Vision of Integrated Dominance

In 1870, at age 31, Rockefeller incorporated the Standard Oil Company of Ohio, partnering with his brother William and chemist Henry Flagler. His vision was deceptively simple yet revolutionary: produce cheaper, refine more efficiently, eliminate waste, and control distribution end-to-end. Kerosene, not crude, was the star—illuminating homes worldwide before Edison’s bulb disrupted it. Standard’s early success stemmed from Rockefeller’s obsessive efficiency: refineries ran like clockwork, minimizing leaks and maximizing output.

Rockefeller’s masterstroke was treating the oil industry as an integrated system, pioneering vertical integration on an unprecedented scale. Standard didn’t just refine; it owned timber tracts for barrels, produced its own sulfuric acid, built pipelines, operated tank cars and wagons, and handled global shipping. This slashed costs—by 1872, Standard refined oil at half the price of rivals—allowing predatory undercutting. Costs plummeted from 58 cents per gallon in 1869 to 8 cents by 1880, democratizing light for millions while bankrolling expansion.

Horizontal integration amplified this. The infamous 1872 “Cleveland Massacre” saw Rockefeller, armed with railroad leverage, buy out 22 of Cleveland’s 26 refineries in six weeks. Competitors faced a stark choice: sell for cash or Standard trust certificates, or endure ruinous price wars. Most capitulated; holdouts were starved via rebates.

Railroad Rebates and the South Improvement Scheme: Controversial Edge

Central to this conquest was Rockefeller’s secret negotiations with railroads like the Pennsylvania, New York Central, and Erie. Forming the South Improvement Company in 1872, Standard guaranteed massive, predictable shipments for rebates—not just discounts, but kickbacks on competitors’ hauls (up to 50% off rivals’ rates). This yielded insurmountable cost advantages and shipment intelligence, turning rails into unwitting allies. Public outrage killed the scheme after leaks, but the template endured: rebates funneled intelligence and margins, fueling the Massacre.

These tactics exemplified Rockefeller’s philosophy: “The growth of a large business is merely a survival of the fittest.” By the 1880s, Standard controlled 90% of U.S. refining, a vast pipeline network, and export dominance, becoming America’s first multinational. Innovation thrived—chemists repurposed “waste” like gasoline (initially worthless) and petroleum jelly (Vaseline). Corporate culture was Spartan and secretive: weekly reports flowed to 26 Broadway headquarters, enforcing data-driven discipline.

The Standard Oil Trust: Legal Innovation and Monopoly Zenith

Interstate laws barred cross-state stock ownership, so in 1882, lawyer Samuel Dodd invented the Standard Oil Trust. Stocks of dozens of companies were surrendered to a nine-trustee board (Rockefeller controlled 41%), creating centralized command without formal merger. This “legal masterpiece” managed a behemoth: 90% refining, global reach, R&D labs. It professionalized management, birthing modern accounting and hierarchies—innovations echoing in today’s Fortune 500.

Backlash, Ida Tarbell, and the Antitrust Reckoning

Dominance bred resentment. Small producers decried “the Octopus,” while journalists like Ida Tarbell—whose father was ruined by Standard—exposed tactics in her 1904 McClure’s series, The History of the Standard Oil Company. Her 19-part exposé, blending rigor and personal vendetta, vilified Rockefeller, coining “monopoly” as a slur.

Politics responded with the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act, targeting “combinations in restraint of trade.” After decades of battles, the 1911 Supreme Court case Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States deemed the trust an “unreasonable” monopoly, ordering dissolution into 34 regional firms. Irony abounded: Rockefeller held shares in all, and rising auto demand rocketed “Baby Standards” like Exxon (NJ), Mobil (NY), Chevron (CA), Amoco (IN), Conoco, Marathon, and Sohio. His wealth, once $400 billion adjusted (per one account), peaked at $900 billion today—cementing him as history’s richest individual.

Philanthropy: Systematic Redemption

Retiring mid-1890s, Rockefeller embraced Carnegie’s “Gospel of Wealth,” viewing riches as a duty. His approach mirrored business: data-driven, scalable impact. Donations topped $500 million (over $15 billion today). Key feats:

Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research (1901, now University): Pioneered virology, yielding Nobel prizes.

University of Chicago (1890s): $80+ million endowment built it from scratch into a titan.

General Education Board (1902): Revolutionized Southern agriculture (via Tuskegee) and Black education.

Rockefeller Foundation (1913): Eradicated hookworm/yellow fever, funded global health—its motto: “promote the well-being of mankind.”

He lived simply—no luxury, strict routines, deep faith—dying May 23, 1937, at 97, attributing fortune to God.

Dual Legacy: Titan of Innovation and Cautionary Robber Baron

Rockefeller’s duality defines him. Positively, he tamed chaos into efficiency, lowering energy costs for billions, inventing the integrated multinational (predecessor to ExxonMobil, Chevron giants), and setting philanthropy benchmarks. His systems—vertical/horizontal integration, trusts, analytics—blueprint modern capitalism.

Negatively, rebates, predation, and coercion stifled competition, embodying Gilded Age excess. He spurred antitrust regimes worldwide, proving concentrated power’s perils. Critics decry corporate greed; admirers praise order from anarchy.

Today, amid Big Tech scrutiny, Rockefeller’s life recurs: efficiency vs. competition, wealth’s public good. Every oil major, foundation, or regulator bears his trace—a case study in ambition’s double edge.

1839 – Birth and Early Years

July 8, 1839 – John Davison Rockefeller is born in Richford, New York, into a modest family. His mother, Eliza Rockefeller, teaches him discipline, saving money, and strong religious values that later shape his lifestyle and business mindset.

1855 – First Job

At the age of 16, Rockefeller gets his first job as a bookkeeper in Cleveland, Ohio. He quickly proves to be extremely skilled with numbers, accounting, and organization. This early experience builds the foundation of his future success.

1859 – First Business Venture

Rockefeller enters business as a commission merchant, trading agricultural goods such as grain and meat. The same year, oil is discovered in Pennsylvania, sparking his interest in the growing oil industry.

1863 – Entry into the Oil Business

Rockefeller invests in his first oil refinery in Cleveland. Instead of drilling oil, he focuses on refining, believing it is safer, more profitable, and easier to control. This decision becomes one of the most important of his career.

1865 – Takes Full Control

Rockefeller buys out his partners and takes full control of the refinery, giving him the authority to apply his cost-cutting and efficiency-focused strategies without resistance.

1870 – Founding of Standard Oil

Rockefeller officially establishes the Standard Oil Company of Ohio. His goal is to refine oil more efficiently than anyone else, reduce waste, and dominate transportation and distribution networks.

1870–1880 – Rapid Expansion

During this decade, Standard Oil grows aggressively:

Rockefeller buys competing refineries

Secures discounted railroad shipping rates

Controls pipelines, storage, and sales

By 1880, Standard Oil controls about 90% of oil refining in the United States.

1882 – Creation of the Standard Oil Trust

Rockefeller forms the Standard Oil Trust, combining multiple companies under one centralized management. This becomes the first major corporate trust in U.S. history and a symbol of monopoly power.

1890 – Antitrust Laws Introduced

The U.S. government passes the Sherman Antitrust Act in response to companies like Standard Oil that hold excessive market power. Public criticism of Rockefeller and monopolies grows.

1897 – Retirement from Daily Business

Rockefeller steps away from active management of Standard Oil, leaving control to others. He begins focusing more on philanthropy and charitable work.

1911 – Standard Oil Broken Up

The U.S. Supreme Court rules that Standard Oil violates antitrust laws. The company is broken into 34 independent companies, including future giants like Exxon, Mobil, and Chevron.

1913 – Rockefeller Foundation Established

Rockefeller creates the Rockefeller Foundation, dedicated to improving global health, education, science, and poverty reduction. It becomes one of the most influential charitable organizations in the world.

1910s–1920s – Philanthropic Peak

Rockefeller donates hundreds of millions of dollars to:

University of Chicago

Medical research institutions

Public health programs worldwide

He becomes a model for modern large-scale philanthropy.

1937 – Death

May 23, 1937 – John D. Rockefeller dies peacefully at the age of 97 in Florida. By this time, he is known not only as an oil tycoon but also as one of history’s greatest philanthropists.

Legacy (After 1937)

Rockefeller’s influence continues through:

Major oil companies formed from Standard Oil

Antitrust laws regulating big corporations

Philanthropic foundations still active today

His life remains a powerful case study in business strategy, corporate power, and social responsibility.